Devil's Club –for that Tropical Look and Feel

One of the most successful shrubs we have in the garden is a

large, and now relatively old, specimen of Devil’s Club, Oplopanax

horridus. Our plant has lived in a pot

for 21 years..or rather a succession of ever larger pots, and now sits on the

cover to our water cistern. I can no longer lift it, so its in the biggest pot

its going to get. In front of it is a clump of exuberant

Trillium kuryabashii which more or less disguises the pot for a good part of

the early growing season.

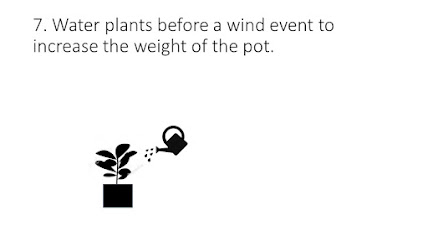

The pot is connected to our drip irrigation system, which

waters most of the garden, including our collection of Brugmansia. Since Brugs and Devil’s Clubs both require a

lot of water to flourish our Devil’s Club has grown to be an imposing specimen.

Most visitors to our garden are impressed with the plant

until they realize what species it truly is, at which point they usually say “Wait

a minute, is that a Devil’s Club?” and give you the same look as if you were

trying to pass counterfeit currency, or sell them cedar kindling sticks as pieces

of the cross. Too many have had bad

experiences hiking through patches of the dangerously armed shrub to have very

many warm fuzzy feelings about the plant, despite its beautiful large leaves

and tropical look.

I was pleased to read Dan Hinkley’s description of the

species as “among the most sensational plants in our natural landscape” – and then

dismayed to read his dismissal from

horticulture as “it simply refuses to survive the transition to a garden

setting” – mental note, don’t let my plant near Hinkley’s book on Shrubs and

Vines.

To be fair, the species for whatever reason, seems to fair

better in the garden confined to a large

container than in the ground, and I really don’t have a good explanation for

why that is so. Ours is on the same

cultivation regime for water and fertilizer as our collection of Brugmansias,

which means lots of both.

It will survive periods of droughts, but then it looks

entirely ratty with dead-edged leaves and dessicated blossom spikes. I suspect the secret to our success is drip

irrigation and an automatic water timer.

Both these things are well worth the effort for this plant,

with it huge leaves and bright red berries the colour of sealing wax. Our plant is now so large that I have had to

chain it down to the lid of the cistern on four sides so that it doesn’t fall over in windstorms. Before we did this, lifting it back up was

quite an effort.

The species is easily propagated by dormant hardwood

cuttings about a foot long, direct stuck

into pots of soil in the autumn and left outside. Its so easily rooted, I’ve never tried

growing it from seed.

Armed with wicked

spines on the twigs and the leaves, its never been the target of deer

browse. Slugs occasionally climb the

spiny stems and chew a few holes in the leaves but never damage the plant to

any great extent.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)